|

Mountain Architecture: An Alternative Design Proposal CHAPTER IV - PART 1 SITE HISTORY: BUILDING ON MOUNT HOOD The development of the Timberline Lodge project is unlike any of the other lodges or hotels mentioned thus far.(1) Popularity of the Mount Hood region as a recreation area had been well established by the mid-1920s, and several small hotels, restaurants, and other support facilities were surviving with little difficulty. What was lacking was a "tourist hotel" capable of accommodating larger numbers of guests for more than just one or two nights. An indication of this need is the fact that by the time formal plans for Timberline Lodge were underway, no less than five, and possibly six, schemes for a large-scale hotel project had been developed, and these all within the preceding ten years. Enthusiasm and interest was not lacking for a hotel project of such a scale, but one obstacle or another (usually financial) had always arisen to squelch the proposals. Timberline Lodge is situated on Mount Hood's south slope, the side of the mountain which remains today the most popular and heavily used. But it was the northern flanks which were preferred for almost all of the early development proposals. It was not until 1934 that any tourist facility was considered for the southern slopes. This occurred above the village of Government Camp, when, as a precursor to the WPA-financed Timberline Lodge Project, a Portland architect by the name of John Yeon, Jr. developed a scheme later promoted by Emerson Griffith to occupy a site very near the present Timberline Lodge. Several small lodges and private chalets did exist on the southern side of the mountain though, and overnight accommodations were available at Government Camp. In 1926 "plans and drawings for a formal compilation of a recreational plan for the southern slope" were drawn up by Francis E. Williamson, Jr., a Forest Service landscape architect. The plan "authorized a lodge at the timber line along with a ski club and mountain climbing club chalets," but the idea seems to have received little, if any, recognition.(2) The first of Mount Hood's mountain retreats was Cloud Cap Inn, an 1889 log structure built to designs by W. H. Whidden, an East Coast architect who had recently arrived in Portland (Figure 4.1). The timber-line site chosen for the structure was adjacent to Cooper Spur on the mountain's northeast slope and at the head of a newly constructed stage road which wound its way up the valley from the town of Hood River, thirty miles to the north. Access was relatively easy, as it involved negotiating the difficult mountain terrain only for the last several miles, and this part of the ride was considered "part of the adventure." Cloud Cap Inn was popular mostly among mountain enthusiasts and served as staging point for many summit climbs and mountain rescue missions. The one-story structure, a long open "V" in plan, hugged the mountain for security and protection against the high winds and heavy snowfalls. Steel cables held it snugly in place. Huge stone fireplaces and the log construction gave it a decidedly rustic character. One early visitor, a Presbyterian pastor from Portland, claimed it was "a thoroughly home-like and hospitable place, a veritable olden time inn." (3) Cloud Cap Inn did not attain much popularity as a resort until the middle 1920s, when large, moderately priced automobiles became available, significantly improving accessability for the less well-to-do motorist. Completion of the loop highway around Mount Hood in 1925 and a new road to the Inn itself also stimulated interest in developing Cloud Cap Inn and its immediate environs into a more substantial tourist attraction. Two separate proposals to further develop the Cloud Cap site were initiated in 1925: one for a hotel backed by the Mount Hood Trail and Wagon Company, and the other for a two-stage tramway from Cloud Cap to the summit of Mount Hood under the direction of the Cascade Development Corporation. Neither of the schemes made it out of the planning stage. The Mount Hood Trail and Wagon Company ran into financial trouble, forcing abandonment of any project to invest large amounts of money in a mountain hotel. The Cascade Development Corporation's tramway proposal went so far beyond what Forest Service policy was capable of handling that the delays of policy re-evaluation and the onset of the Depression eventually made it unrealistic to pursue.

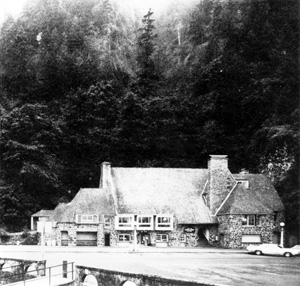

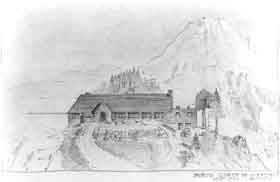

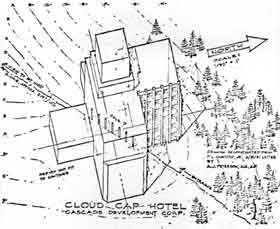

Despite the financial infeasibility of the two projects, they both progressed well into the design stages before being terminated. For the hotel proposal, the Mount Hood Trail and Wagon Company hired architect A. E. Doyle of Portland to execute its design. Although none of Doyle's sketches survive, it was to follow the Picturesque style along the lines of his Multnomah Falls Lodge of 1923 (Figure 4.2). Jean Weir in "Timberline Lodge: A WPA Experiment in Arts and Crafts," comments: "Doyle proposed a rambling hotel of a kind close in spirit to European mountain chalets; he may have had in mind something resembling the chalet at Oregon Caves National Monument [Figure 4.3], built only a few years earlier. The newspaper description stated it was to be built in stages with a dining room, and a few overnight rooms put up first with additions planned for later." (4) Whidden's original Cloud Cap Inn was to be eventually torn down. Pietro Belluschi, on his way to eventually becoming one of the pioneers of northwest regional architectural design, joined Doyle's office in 1925 and shortly thereafter illustrated a design for a new Cloud Cap Inn (Figures 4.4 and 4.5). Opinions differ as to whether it was intended as an addition to the 1889 structure or was just a refined version of Doyle's original scheme, to stand independent of Cloud Cap Inn and eventually replace it.(5) In any case, it was substantially different than Doyle's. Although still in the Picturesque mode, it is noted by Weir as "less playful and less elaborately decorative than the older, more traditionally-minded examples of the Picturesque style standing in the region." (6) Meanwhile, Cascade Development Corporation was developing plans for its proposal, but with a completely different architectural intent. They too had designs for a hotel to accompany their scheme for a tramway to the summit. It was to be nothing like the picturesque or rustic designs so far existing or proposed for the Mount Hood region. In the words of Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who wrote critically of it in a 1931 memorandum to Chief Forester R. Y. Stuart, it exhibited "a type of treatment appropriate to skyscrapers towering aloft from city streets or a monumental structure on a broad plain." (7) It was clearly not suited for a site anything like Cloud Cap. The architect appears to have been Carl Linde of Portland. A recent reconstruction drawing based on the Olmsted memorandum (Figure 4.7), and a photo of an early model (Figure 4.6) give some indication of the design. John Yeon (to whom at least one source (8) incorrectly attributes the design) remembers the scheme as,

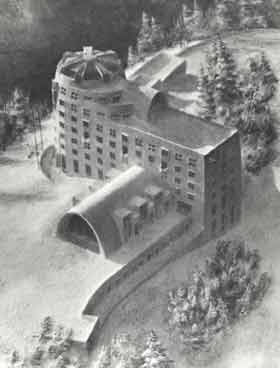

Olmsted had become involved in the project as the chairman of a three member commission appointed by the Forest Service to evaluate the Recreational Complex proposal put forth by the Cascade Development Corporation. They were also to concurrently develop a management plan for the Mount Hood National Forest region. The resulting lengthy report, Public Values of the Mount Hood Area, set the tone for future development on the mountain and effectively quashed the proposal with such comments as, in a specific reference to the hotel, "[it was] a gratuitously conspicuous contradiction of the wild and unsophisticated character of the scenery." (10) It wasn't until 1931, five years after the first permit application, that the Cascade Development Corporation gave up. The last major project to be developed for the north slope was also for the Cloud Cap site. John Yeon, Jr. had developed a daring hotel design for which he hoped he could attract local promotion. He had been a vocal opponent of the Cascade Development Corporation's tramway project, and knew well the virtues of the site which had brought previous entrepreneurs back to Cloud Cap again and again--the magnificent scenery and unparalleled views of Mount Hood's rugged north side.

Yeon's design was very modern, likely the first of its kind in a mountain setting--certainly much more of a statement about architecture than any of the previous schemes for the site. Yeon, in a letter to the author, comments on his 1931 design (Figure 4.8):

Despite the resolution and continuity of the design, by the time Yeon had completed the large presentation model, he had experienced "crashing disenchantment" with both the design, and Cloud Cap as a site:

This last scheme eventially died, not by cries of outrage over its design (which evidently was supported by the state's governor, and was on public display in model form in a downtown department store window), but by attrition and the economic timorousness of the Depression.

Continue to CHAPTER IV - PART 2 Master of Architecture Thesis |